Q&A: Engineer Stewart Isaacs seeks equitable climate change solutions

In an interview with Physics Today, postdoctoral fellow Stewart Isaacs discusses his research and work supporting communities in need, his commitment to addressing climate change, and where his passion for jump rope fits into it all.

Stewart Isaacs got interested in developing solar-powered chicken egg incubators in 2016, when he was an undergraduate student. The project’s goal of supporting self-determination and food sovereignty in West Africa resonated with his desire to use his engineering skills to support communities in need and break down inequities. “I liked what the incubator project was trying to do,” he says, “but I didn’t think it would be interesting technically. I was wrong.”

Even as he pursued a master’s degree in aeronautics and astronautics, Isaacs kept a hand in the ongoing egg incubator project. He visited Burkina Faso to see the project in action. Then, in 2019, when he finished his master’s, he flew to Ghana to learn more. Propelled by nagging questions about the incubators’ solar power conversion, he decided to go for a PhD, which he earned this past May. He is now a postdoctoral fellow at MIT pursuing research that addresses both climate change and social inequities through the development of clean energy systems.

Aside from his research, another passion of Isaacs’s is the sport of jump rope. He won the 2017 Grand World Championship in single rope freestyle.

PT: How did you get involved in solar-powered egg incubators?

ISAACS: When I was a senior at Stanford University, I met Dena Montague, a researcher from the University of California, Santa Barbara, who was looking for students to support her in developing solar-powered chicken egg incubators for use in West Africa. The project was well aligned with my goals: I was interested in using my skills to support communities in need, especially Black communities.

It took a few years before we got to the point where the incubators were functional. One of our primary design goals was for the system to be locally manufacturable, so that when things inevitably break, the users can fix the incubators and make sure they meet their needs.

PT: What did you do in Ghana?

ISAACS: Dena has a nonprofit, ÉnergieRich, that initially worked with a community in Burkina Faso. I didn’t think MIT would pay for a trip to Burkina Faso because the US State Department had a Level 3 warning about travel there, so I went to neighboring Ghana. I thought it would be a nearby alternative, where I could still learn and start to question some of the assumptions I had.

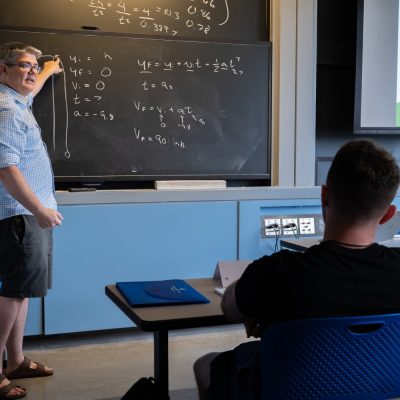

While I was there, I looked for partners to support the development of the incubators. I also accepted a position as a teaching fellow at Ashesi University. I taught mechanics and thermodynamics. And I learned a lot from my students—especially about how to live without infrastructure, like how to store water in large containers in case the water goes out and to ensure electronics stay charged for if the power goes out.

PT: What were some of the assumptions you were questioning?

ISAACS: I didn’t think there was a lot of manufacturing capability in the region, but there is. A lot of people have programming skills and access to technology.

Another thing I learned was that the solar panels were not converting as much energy as we had calculated. Ultimately, that problem led me into my research for my PhD.