The centenarian alum reflects on a lifetime of aeronautical innovation, retirement adventures, and the timeless spirit of MIT.

On August 24, 2024, Quentin passed away peacefully, surrounded by his loved ones. His presence will be profoundly missed by the family and friends who were fortunate to share in his remarkable life. His obituary is posted in the Port Townsend Leader.

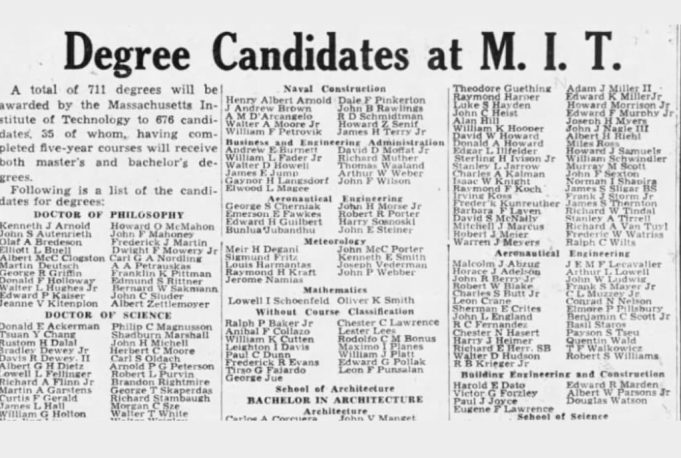

The 1940s were a time of tremendous advancements in aeronautics. Igor Sikorsky set a national record in helicopter flight, the U.S. Army Air Force was established, and the first jet engines took flight. And in 1941, Quentin Wald, who celebrated his 104th birthday on June 4th, 2024, graduated from what was then MIT’s Department of Aeronautical Engineering – and saw it all.

Prof. Earll Murman, head of the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics from 1990-96, met Wald by chance when they both ended up in the town of Port Townsend, Washington in their retirement and joined a breakfast club for sharing ideas and socializing. Following many years of friendship, it was Murman who suggested capturing Wald’s unique experience in an oral history.

Wald was inspired to pursue a career in aviation by his father, who trained as an aircraft machinist and pilot at the Wright Company Factory in Dayton, Ohio – with Wilbur and Orville Wright themselves. He often took Wald to work with him when he later worked as an inspector on naval seaplanes.

“I still remember the smell of aircraft factories when airplanes were built of wood and covered with “doped” fabric. I never wanted to be anything but an aeronautical engineer from the time I first knew the words. I wanted to design airplanes,” he said. “Then when I got to MIT, I knew I didn’t want to design – I wanted to understand.”

A timeless MIT student experience

In 1937, Wald rented a room in Cambridge and began his academic career. He recalls his experience as a student with a reverence for the academic rigor that drew him to MIT. “It was always a stimulating environment,” he said. “I was very busy.”

As an undergraduate, Wald was a member of the Glider Club, where he finally gained firsthand experience in aviation by piloting—and once, crashing—a glider. “The launching area was a flat and clear space – but I found myself descending to Earth in an area which was not flat and clear,” said Wald. “The glider was not ruined – but it was a clumsy effort.”

“There was no faculty supervision whatsoever,” he added.

Wald’s senior thesis explored the stability of helicopters, a topic suggested by his future employer Igor Sikorsky, founder of the Sikorsky Aircraft Corporation. The paper was awarded the James Mean Memorial Prize for the best undergraduate thesis on an aeronautical subject, and launched Wald into a career in hydrodynamics and aeronautical engineering research. Craving a deeper understanding of mathematics, he returned to MIT and received his masters degree in 1960.

From taking flight to setting sail

Following a long and successful career focused on hydrodynamics, Wald retired at 65 and embarked on a new adventure. He sold his home and flew to Europe, where he bought a boat that he called the Anaximander, after the early Greek philosopher “whom I admired because he seems to have been the first to conceive that the earth floated in a space without a preferred direction,” said Wald.

He spent three years sailing in the Mediterranean and Aegean Seas, exploring the islands and meeting new friends. He has since sailed up and down the coasts, across the Atlantic, and weathered a hurricane, before making port in Washington near his three children and grandchildren. He also began writing essays and books, including “My Life as an Engineer,” “The Wright Brothers as Engineers, an Appraisal,” and a research paper on “The Aerodynamics of Propellers.”

During his time at sea, Wald began to write poetry, or “thoughtful bits that I thought might be poetry,” as he describes it. His creative outlet later led to the publication of his book, “The Farthest Shore,” a collection of his poetry. Murman and other friends at the Tuesday breakfast club put together a second book for his 100th birthday in 2020, with more of his poetry and writing, as well as an autobiography of his life.

“My professional years were very interesting, but then when I retired, I wanted a much more varied life,” he said.

Murman and Wald still attend their breakfast club meetings each Tuesday. He still writes poems about his travels, his life, and the intersection of math, science, and art – the intersection where he now sits, surrounded by friends.